The value of waste: Small-scale waste management as gateway to social and solidarity economy, women’s empowerment, and the promotion of eco-tourism

Where do we stand on the map?

Morocco is a country with a rich multicultural, patrimonial tapestry. Throughout its history, the country expanded across other lands and was home to many cultures that have left indelible marks on Moroccan identity, language, clothing styles, cuisine, and rituals. When we speak of multi-culturalism, we can see elements of an indigenous Amazigh culture, Roman and Phoenician influences, African roots and European windows, as well as Jewish and Islamic-Arab components. This all combines to create a very versatile, diverse, yet unified and indivisible Moroccan cultural identity. Exemplifying this rich cultural mosaic is the small city nested at the foot of the Middle Atlas Mountains, Sefrou, only 22 km (20-40 minutes by car) from the former imperial and currently spiritual capital of Morocco, Fes.

Often overshadowed by the lure of the larger neighbouring cities, Sefrou does not get the exposure and fame that it deserves, nor does the haphazard one-day trip to its old medina help in changing the status-quo.

Sefrou was once home to the largest Jewish population that lived in Morocco, represented a crossroads for trading caravans connecting the south of the continent to the north, and was a strategic niche for Morocco’s historical settlers, the Phoenicians and Romans. Besides this versatile history, my investigation led me to the conclusion that indeed there is more than meets the eye in this city. Over the years, the old medina of Sefrou has developed a sustainable, green waste-management system through its humble economic activities. Interestingly, the circle of production is invisible, and production, repurposing and reproduction dominate the city’s small industry cycles. The priority for these artisans and their indicator of success is reducing waste at the source and making sure that everything can be reused for a second, third and fourth production. Three foundouqs[1] are leading this eco-friendly trend: Foudouq Laghzel, Foudouk Al Haddadin, Foundouq Ahl Fès. At every turn and cornver, everything you see on display is recycled, from chairs and plants pots to bags and clothes. Everything has its place, and everything is given a second chance at life.

Let’s take a step back to understand the full picture!

1,672,919,332 tons of household waste were generated globally when I visited the World Counts website this past October. Watching the numbers increase every second was frightening. Every year, humans produce millions of tons of waste, only 20 % of which goes to recycling. In the best cases, the rest is laid to rest in landfills in the best cases, but it is also discarded in the deep bellies of the oceans and in hazardous open dump sites around the world, often close to where the most vulnerable populations live. A recent World Bank report predicts these numbers to increase to 3.4 billion tons by 2050 and to triple in low-income countries, including sub-Saharan Africa.

In Morocco alone, 26.8 million tons of waste was generated in 2019. According to figures published by the National Strategy for Waste Reduction Conversion, this production was split between 7.4 million tons of household waste (an average of 0.76 kg per inhabitant every day), 5.4 million tons of industrial waste (2017), and 14 million tons of construction and demolition waste (2019). The same report estimated the expected growth of waste production would reach 39 million tons by 2030.

Economic growth and urbanization are key factors in the increasing scale of waste generation. In recent years, Morocco has become a competitive African station for foreign and national industrial investments (aeronautics, automobiles, textile, and agriculture). The urbanization rate has also exponentially increased from 58 % to 64 % between 2011 and 2022. This constant growth is putting a heavy pressure on the country, as effective waste management becomes an imminent need to respond to the rapid increase of waste generation, especially given that only 10 % of the overall waste produced in 2015 went to recycling.

In response to these trends, Morocco has put in place several legal and institutional measures that include:

- Law 28-00 was published in BO n°5480 on December 7, 2006: This law defines the different types of waste, specifies their method of management, and specifies the level of their management. It also introduces the concept of hazardous waste and the management of this type of waste by subjecting it to a system of prior authorization at all stages of management: collection, transport, storage, and disposal. The law also lays down rules for the organization of existing landfills and calls for their replacement by controlled landfills, which will be classified into three distinct categories according to the type of waste they will be authorized to receive. The overall purpose of this law, as stated in article one is: “to prevent and protect human health, the fauna, flora, water, air, soil, ecosystems, sites and landscapes and the environment in general against the harmful effects of waste”.

- Morocco has also made serious efforts to stop producing and selling plastic bags, where 26 billion were being used in the country on an annual basis (900/person per year). This was done through law No. 75-15, known as the “Zero Mika law”, enacted in 2016.

- The launch of the National Household Waste Program (PNDM) with an estimated budget of 40 billion dirhams. This program was developed by the State Secretary for Sustainable Development and the Ministry of the Interior with the support of the World Bank as part of the national policy to reform and develop the household waste management sector. This project aims to:

- Ensure the collection and cleaning of household waste to achieve a collection rate of 85% in 2016 and 90% in 2020.

- Create landfill and recovery centers for the benefit of all urban centers (100%) in 2020.

- Develop the “sorting-recycling-recovery” sector, with pilot sorting schemes, to reach a recycling rate of 20% by 2020.

- Generalize master plans for managing household and similar waste for all the country’s prefectures and provinces.

Micro, small, and medium-sized businesses have been playing a key front-line role in advancing Morocco’s strategies for sustainable waste management. There are many examples across the country, taking us back to the small city of Sefrou!

Unlimited chances at life

I have worked in Morocco’s smallest museum, situated at the heart of Sefrou’s old medina. There I conducted ethnographic research, met the people of the mellah, and witnessed the waves of Moroccan Jews coming back to the remnants of what was before their ancestral “home”. In the eleven months I spent there, I witnessed how the old medina regenerated itself in a way unlike anywhere else. An invisible circular motion of production, revalorization and repurposing shaped all industrial actions. What was normal to the artisans of the old medina, was remarkable to me.

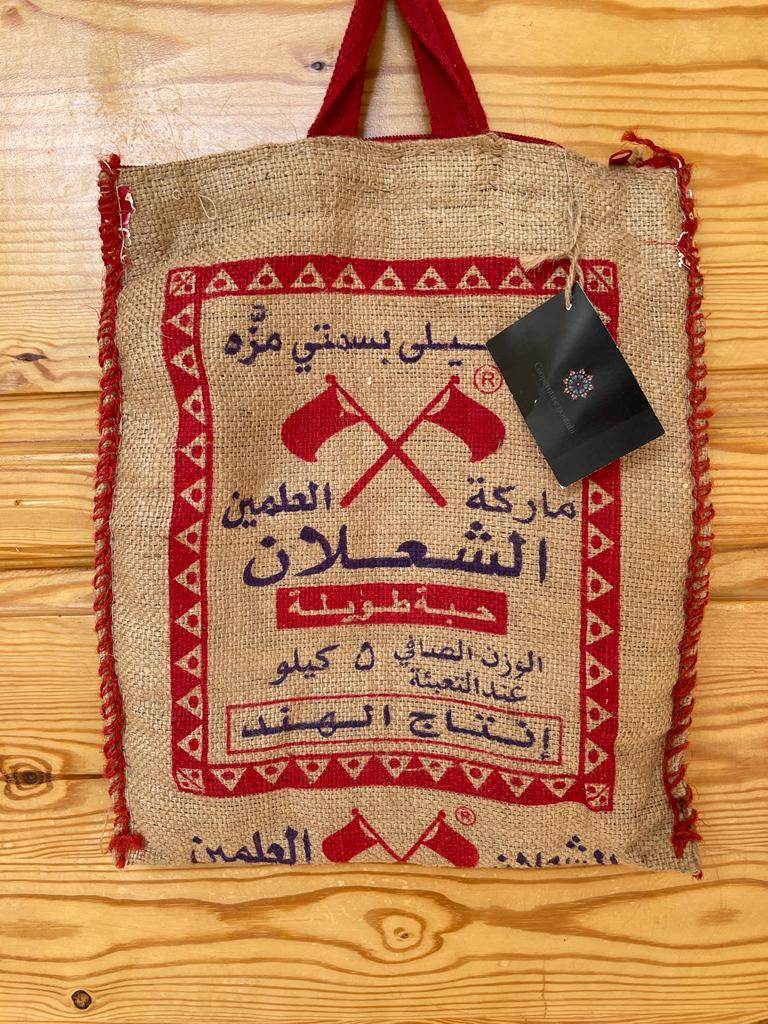

The left-over metal was often reshaped to make the little teacup hooks that Ami Abdessalam used in his tea shop. A little shop cornered in front of the oldest tree in the medina, and one of the last surviving traditional tea houses in Morocco. Egg boxes collected from the nearby restaurants were turned into chairs found in every little shop or workshop in the area. Old flour plastic sacks collected from the neighborhood’s ovens and used by women and artisans alike to create carpets and all sorts of house decorations.

In foundouq Laghzel I had the chance of meeting Karima, a 31-year-old woman making her way into the world of entrepreneurship through eco-friendly projects. Once I told her about the topic of my article, Karima smiled and showed me her everyday handbag. Recycled from old straw and curtain rings. Karima had stitched the rings to the front of the bag after redecorating them with scrap metal that she collected from her training workshop. Karima stated, “as we give a second life to everything here, this work has given me a second chance at life too. After my divorce 7 years ago, I found myself with nothing. Two girls in my care, no possessions, no job, no future in sight”.

Married at the age of 17, Karima found herself in the middle of a whirlwind after divorce. To look after her two daughters, Karima took on several jobs: an elementary school teacher, a secretary, and an assistant. Now, Karima is all about establishing her own business, using eco-friendly materials only, “when I discovered this place (referring to the foundouq), I decided to come every day to learn how to sew. I spent two years here before starting my own project. Ever since, I have taken it upon myself to seize any opportunity to develop myself and create my own start-up. I chose to work on eco-products because not only does it save our environment, but it also gives me the power to wake up every day and do my work. It gives me a sense of meaning. It makes me feel important because I see the impact of my work on myself and my surroundings.”

In the three foundouqs of Sefrou’s old media, all workshops operate in the same way. Nothing goes to waste. Scraps of thread are reused for children’s clothes. Djellaba buttons are recreated into jewelry. This business has attracted many tourists and has allowed the artisans to expand their work to include craft workshops for international fashion students. One notable example that was continually mentioned by all the artisans was that of Amina, one of the oldest dressmakers in the old medina. Because of her work recycling buttons, Amina got the chance to showcase her crafts all over the world, including America, everyone insisted! Today, Amina owns one of the largest workshops in the Artisanal chamber of the city. Her work attracts admirers and students from all over the world.

For these artisans, recycling has become a valuable trade and a new business approach that generates both material and immaterial benefits.

Connected threads: when the past informs the future

Wherever you walk in the old medina of Sefrou you see colorful pieces hung over the walls, on chairs and sofas, as door mats and sometimes as winter bedcovers. Boucharouite (pieces of rag) is a tradition that still has value and life in this city. From an Amazigh origin, boucharouite can be considered as one of the oldest ways that our ancestors revalorized their possessions.

The recipe for making these beautiful rugs is simple: all you would need is old fabric (rags, clothes, wool, cotton, or nylon threads). For the artisans of Sefrou’s old medina, rags exist in abundance. The second thing that you would need is a large-sized plastic sack from the local oven. The next step would be to cut the cloth into strips, knitting them tightly into the sack and voilà, the tapestry is ready for use.

Stories about boucharouite in the medina are abundant. L’maalem Mohammed from foundouq Al -Haddadin shared his story with me as he taught me how to create a piece myself. He recounted that his mother used to collect their old clothes, cloths, or even nappies. Once a year, she would tear all the fabric she collected into small strips, mixing them to get the right combination of colors she wanted. Then, she would take any perforated fabric available and start to stitch the pieces together to her liking. Most of the rugs made in this way carried traditional Amazigh symbols.

5,000km from Sefrou to Amman: the journey continues

There are more than 5,000km between the small city of Sefrou from the Jordanian capital, Amman. After almost a 19-hour journey, I immediately started looking for connections in this new setting to guide me on my quest for innovative ways of waste management. Alia Ecovillage was my first stop. This facility is described as a “project functioning as environmental education, activism and advocacy hub”. According to Khaled Shorman the founder and manager of this facility, the Alia EcoVillage is built as an antidote to mass consumption. It is a way of bringing people closer to nature, to the older ways of life, where people were able to. Live off what the earth produced. Sary, a volunteer at the village was my guide on this journey. 11 years ago in 2011, he moved to Jordan from Syria, his country of origin, after the war broke out.

In his childhood, Sary stated that his family recycled all its belongings, “perhaps we did not have a lot, that’s why we saw the value of reusing and repurposing everything. We used buckets instead of plastic bags, we reused our clothes between siblings, and we collected rainfall water for cleaning. As kids, we also made our own toys out of bottle lids and plastic straws. All the children in the neighborhood did the same. We did not have money to buy new toys, so we made our own”.

After a few years of living in Amman, Sary lost his job, and with more time on his hands, he decided to take care of his neighborhood garden. However, as he had no budget, he decided to resort to recycling, igniting his passion for this work.

In his current position at the Alia Ecovillage, Sary works primarily on collecting household waste from Ammam by using his network of NGOs and start-ups working in the field. He then recycles all the waste for the village. Some of the work includes decoration, planting, and repurposing.

Alia Ecovillage is a model for an eco-friendly tourism business. When finished, this town will offer accommodation and catering facilities in completely green and sustainable settings. Already, it hosts a large community of national and international volunteers. All driven by their love and care for the environment.

Imperfection is also a fundamental piece of the puzzle

Recycling is simply not for everyone:

Although many young people see the profitable value of recycling as an innovative business model, generating a decent income for new start-ups and helping the future of our planet, experience shows that not all people share this same keen interest. “The absence of a recycling culture is driving people to constantly seek new things, without thinking twice about the actual value of what they already have”. FatimaZahrae, a young entrepreneur originally from Salé started her project “Sew Me” in 2020 during the COVID-19 lockdown in Morocco. A building design graduate, FatimaZahrae found herself unemployed when COVID-19 struck. She decided afterwards to turn her DIY hobby into a profession. “My idea was to teach people how to turn their old clothes into something new that they can wear again. I started making videos and sharing them on the internet with the hope of inspiring young people, especially since thrifting culture had started to gain momentum in the country and that there were many active local projects”. After numerous attempts to grow her business audience, FatimaZahrae decided to shift her activity because she discovered it was too niche to establish a robust start-up for recycling. For FatimaZahrae, people are still resistant to the idea of turning old into new: “people wanted me to make their clothes for them, I was unable to do that because that was not part of my business model then and because I didn’t have the means to. I found that people prefer to buy new rather than repurpose what they have already, and which in most cases is very usable”. Now, FatimaZahrae has established a new business of making eco-friendly jewelry out of natural clay. Her business involves an online store where she sells her handicrafts, in addition to delivering several workshops where she shares her skills with those interested in making jewelry or in starting their small business in the field. I have recently started a new partnership where I deliver workshops to sub-Saharan migrants to help them learn new skills and develop new income-generating activities: “clay does not have an expiration date; it offers unlimited creative potential and can be easily fixed if it’s broken or if we want to remodel it”.

Despite the efforts from governments, civil society, and the private sector, we are still a long way from building a national (let alone global) structure of sustainable waste management. Besides the high costs of recycling, small-scale, businesses initiatives led in solidarity only cover a fraction of the millions of tons of waste produced every year. With the limited resources and skills available, these initiatives remain incapable to upscale the scope of their work, their beneficiaries, and their employees, and consequently, their social and ecological footprint. In addition to this, the artisans I visited (some of whom were covered in this text) remain incapable of broadening the spectrum of their work because of a lack of technical skills and resources such as, marketing, e-commerce, and innovation training. Covid-19 played a major role in shifting the way they approach their businesses, but still, most of them are unable to make their visions a reality while meeting market demands on one hand, and of thinking and working sustainably on the other.

Imagining a way forward

What could be the way out of this deadlock? How can we contribute to shifting conditions when millions of tons of waste are generated every year? It almost seems like an impossible mission, an elusive dream even.

In my opinion, the way forward starts with building an awareness about how much we consume and produce. It starts with us seeking balance in our lives and being aware of our actions. By educating ourselves, we can change our ways, and we can then help influence other people’s behavior around us.

Putting a stop to waste is impossible, but putting a stop to our careless ways of managing waste is, nonetheless, very possible and within our reach.

Sara El Ouerhiri

[1] Foundouq or funduq, also known as caravansarai or traveller inns were rest stops for travellers and merchants across ancient trading routes. These buildings provided lodging, supplies, and a networking hub for those coming from afar. Today, the surviving foundouqs in the city of Sefrou serve as commercial centres hosting the cities’ artisanal workshops, such as carpentry, tapestry, weaving, traditional and modern couture.

![]() Ce reportage a été réalisé dans le cadre de MediaLab Environnement, un programme conçu par CFI financé par le Ministère français de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères. MediaLab Environnement s’inscrit dans la stratégie internationale pour la langue française et le plurilinguisme.

Ce reportage a été réalisé dans le cadre de MediaLab Environnement, un programme conçu par CFI financé par le Ministère français de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères. MediaLab Environnement s’inscrit dans la stratégie internationale pour la langue française et le plurilinguisme.

Sara El Ouedrhiri est doctorante spécialisée en études de genre. Ses recherches portent sur l’intersection entre le droit, la théologie et les violences basées sur le genre. Elle est militante féministe et défenseuse du développement humanitaire participatif, global et inclusif. Son parcours professionnel combine l’action civile et académique. Elle s’intéresse aux droits humains et aux questions de genre, à l’autonomisation des jeunes, ainsi qu’aux arts, au dialogue interculturel et à la préservation culturelle.